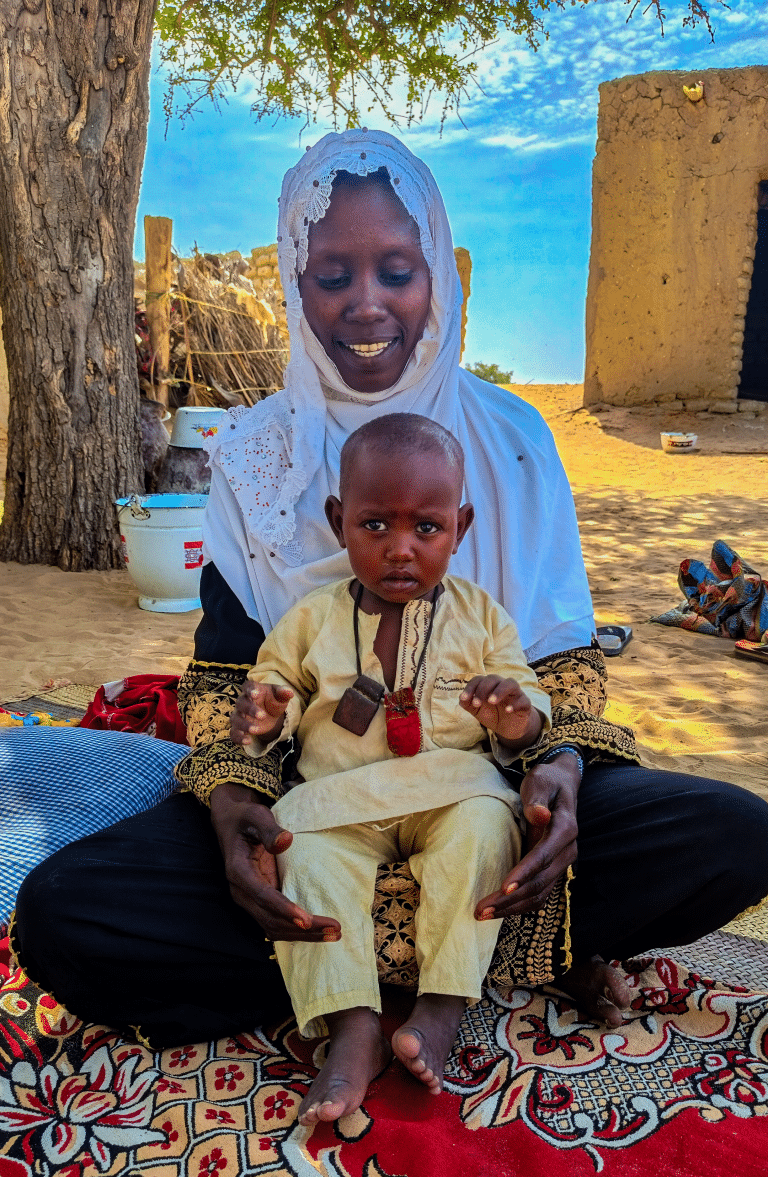

“I thought that malnutrition was due to becoming pregnant at a young age,” Zalissa said.

But now, thanks to trainings that are happening in communities in the central region of Burkina Faso, Zalissa and some 55,000 other mothers have learned what malnutrition is and how to detect it.

“We found the training to be simple and were able to pose many questions,” she said. “I understand now, from the training, that malnutrition is related to diet.”

The trainings are part of a program in which ALIMA and its partners are trying to change the way people fight malnutrition.

The technique is simple: teach caregivers to detect malnutrition early, using a simple, colored bracelet, known as the MUAC, which measures the upper arm circumference of children under the age of five.

If the child’s arm measures in the green zone, he or she is not malnourished. If it shows yellow, it means the child is at risk of malnutrition and if it measures in the red zone, the child is suffering from malnutrition.

Each mother is told to take their child to the health center if the bracelet shows yellow or red, and also taught how to prepare nutritious, well-balanced meals, to avoid malnutrition.

“The animator showed us first how to use the MUAC and then we practiced it,” said 36-year-old Germaine, a mother of four, who also attended a training in her village. “Thanks to the colors, it is easy for those of us who don’t know how to read. Once you understand how to use it, it’s very simple.”

Another thing the mothers all liked is that the MUAC can be used at home and on a daily or weekly basis.

This is particularly important in rural villages where people often live far from health centers, and during the rainy season when roads are bad and families are working in the fields all day and can’t bring their children in for regular check-ups.

Early detection of malnutrition is key to avoiding hospitalization and could save lives. In Burkina Faso, survey data from 2016 showed an estimated 7.6 percent of children under the age of five suffered from global acute malnutrition and 1.4 percent were severely malnourished.

The initial goal of the MUAC project, which focused on mothers, was to train 41,000 women in 2016 to screen their children for malnutrition. Teams ended up training more than 70,000 people, including 55,000 mothers of children between the ages of six months and five years. The number of caregivers in Burkina Faso who learned to use the MUAC is even higher, as the women who ALIMA and its partners trained often passed on what they learned to friends and family.

“When I talk with my neighbors, I remind them to regularly use the MUAC,” said Brigitte, a 40-year old mother from the district of Yako who discovered her two-year-old niece, whom she cares for, was malnourished after using the MUAC bracelet. “If, one day, I travel to another region, I can explain to women there who don’t know what it is. Even if I can’t give them a MUAC, they will have an idea of what is malnutrition.”

Justine, who lives with her husband and their eight-month-old daughter in central Burkina Faso, said that after the training she taught her husband how to measure their daughter’s arm and detect malnutrition using the MUAC.

“It would be great if the men could also participate so that they can help mothers, who because of a lot of work, are very busy,” Justine said. “It’s already great that women have been trained, but now we can show others how to use it.”

Since January 2017, ALIMA teams have trained nearly 30,000 mothers to use the MUAC and offered refresher courses to many of the mothers trained in 2016.

ALIMA has been working in Burkina Faso since 2012. Currently, ALIMA is conducting a medical-nutritional project in the district of Yako, in partnership with two national medical organizations, SOS Doctors and the Association Keoogo. Together, they support more than 50 health centers.. More than 4,500 children with severe acute malnutrition were admitted to ALIMA’s nutritional programs in 2016.