In 2022, 3.4 million people were deprived of assistance and protection, including 2 million with particularly severe humanitarian needs. Maternal and infant mortality rates are the fifth highest in the world, with 829 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births, and 103 infant deaths for every 1,000 children under the age of five ².

In this type of particularly complex context, ALIMA works hard to give access to health care to populations that have been most impacted, or even physically and psychologically traumatized.

Since October 2022, ALIMA has been working in the maternity ward of the Castors Health Center, located in the heart of Bangui, the country’s capital. The NGO began by rehabilitating the health center, building the capacity of the staff (national midwives, matrons, neonatology assistants) and supporting operations of the maternity unit. ALIMA also organized awareness campaigns to inform the district’s population of the free quality care available at the center.The aim is to improve access to health care in the district, particularly in the areas of sexual and reproductive health, family planning, mental health and psychosocial support.

Gypsie Christelle Nambozouina, 30, is a clinical psychologist at the Castors maternity hospital. She tells us about her day-to-day work and what the people of the Central African Republic are going through, particularly women and children, in an unstable security context.

What is it like to be a clinical psychologist in this maternity hospital?

My work is to provide psychological support for distressed patients and their families. The center welcomes women with very different problems who require comprehensive support. For example, we receive pregnant women who need a Cesarean section to give birth; I prepare them mentally before they go into the operating room, as many of them have fears and intrusive thoughts, or. unpleasant images that come back and can generate anxiety.

I also follow up with women who have just given birth and turn out to be HIV-positive. Some are unaware of it… I have to tell them and give them psychological support before referring them to the HIV department, where they will receive treatment. I also see women whose pregnancies have unfortunately ended prematurely, or in other cases, fetal deaths, stillbirths or abortion-related complications.

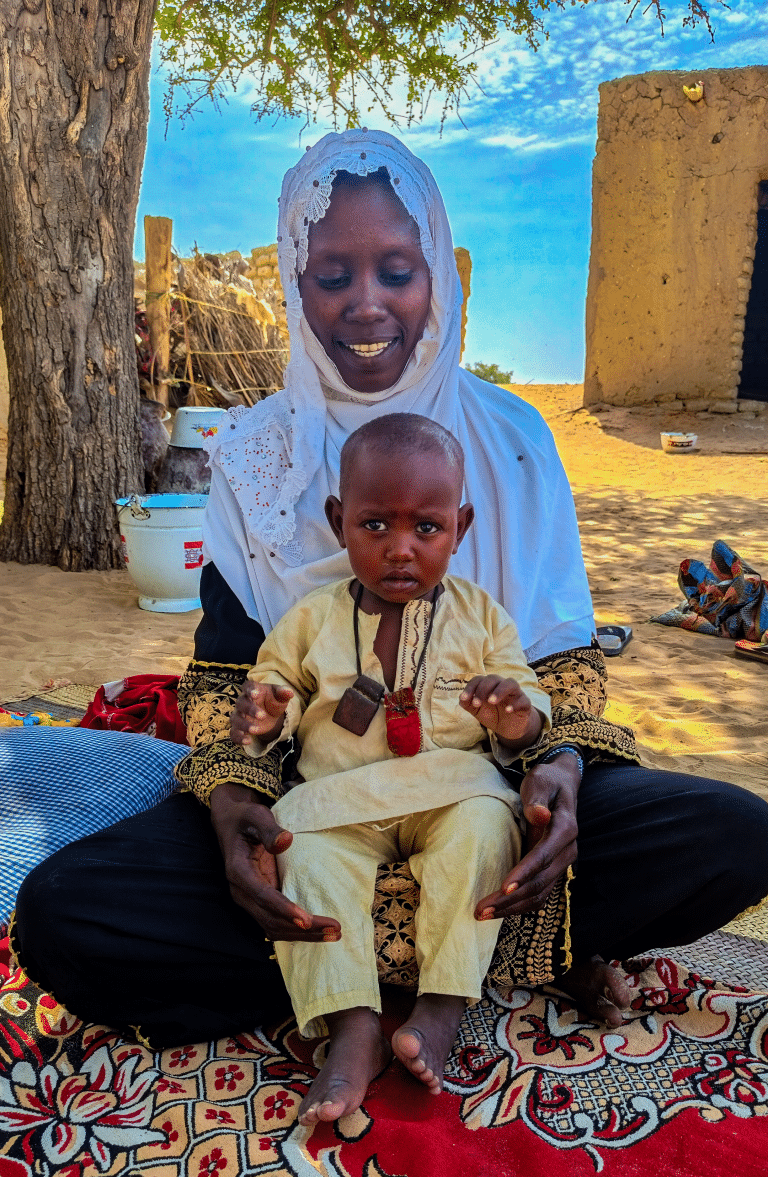

At the same time, I work on gender-based violence (GBV). We receive a lot of cases of violence that require essential psychological follow-up: rape, sexual assault, psychological violence, physical violence, denial of pregnancy linked to violence, and so on. We mainly see women, but sometimes children too…

Awareness-raising illustration on the wall of the maternity ward at the Castors Health Center. February 2023. Bangui, Central African Republic. © Cora Portais / ALIMA

Does the country’s security context influence gender-based violence?

There are many causes of GBV. We receive many cases of psychological violence linked to the abandonment of women by their husbands and surviving rape. It’s clear that insecurity in the CAR encourages gender-based violence and has a major impact on patients’ sexual health.

I organize psychoeducation sessions for patients’ relatives to raise awareness of violence against women and the consequences for their sexual and mental health. This is necessary to raise public awareness and bring about change.

What motivates you in providing such difficult support?

I studied here, in my country. After my secondary education diploma, I did a first year in sociology. I passed, but then I learned that a new department of psychology had been created at Bangui University. One of my professors explained to me that this new department was created to better cope with the events the country was going through [two civil wars in 2012 and 2013, editor’s note]. “Many people are going to have more and more psychological disorders,” he told me. “Among other things, war leads to violence and death, and mental health support helps families.” Bangui University trains around 50 new psychologists every year.

This conversation shaped my career: I obtained my Master 1 in psychology, and since then I’ve worked for several NGOs.Secondly, as a woman, I like to support other women who are suffering and help them achieve mental equilibrium. It’s rewarding to contribute to the good health of patients. I’m proud to work with Central African women, and more broadly, through the women I support, I’m supporting my country’s entire population.

Portrait of Gypsie Christelle Nambozouina, clinical psychologist on the sexual and reproductive health project at the Castors Health Center. February 2023. Bangui, Central African Republic. © Cora Portais / ALIMA

What stories have particularly impressed you?

All the patients’ stories have touched my heart.

Childbirth is always a moving experience. I can immediately feel the pain of certain women who come to give birth and for whom it’s difficult. Sometimes they express themselves, sometimes they cry. When it’s a woman or a girl’s first time to give birth, we call it “the first steps.” I like to be with them, to support them psychologically.When HIV-positive women are ready to go home, I call them regularly to support them, encourage them to accept and continue their treatment. Patients often come back here to thank me, and that’s something I’m very proud of.

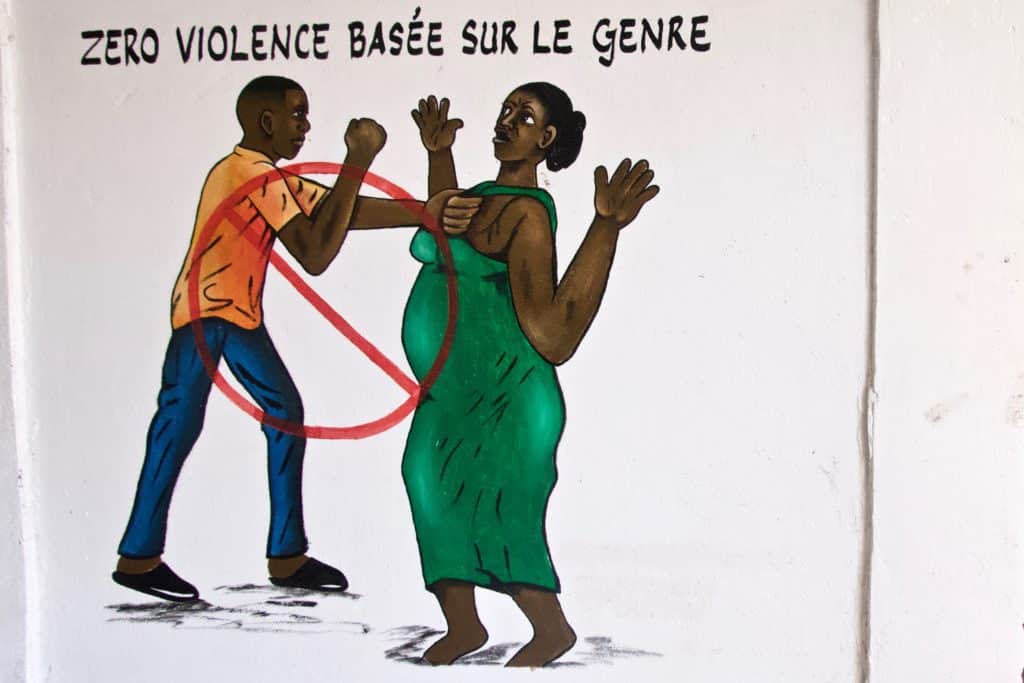

Portrait of Floranie Malizeno and her newborn baby girl at the Castors Health Center maternity ward. “This is my first child. My delivery went well. The health workers here are very attentive.” © Cora Portais / ALIMA

What are your dreams for yourself and your country?

I’m the only psychologist working on this sexual and reproductive health project. I see a lot of patients and would like to be helped by other psychologists on the project. As we speak, five patients and their caregivers are waiting for me, not to mention those waiting in the emergency room. I run this department on my own, and I try to follow each patient carefully, but I can’t do any more than that.I give a lot of my time and energy to patients, because in my opinion, the work I do is essential in this security context. Violence is rife in my country, particularly against women and children. Many women lose their lives giving birth. I believe that there can be no health, or sexual and reproductive health, without mental health. The balance has to be both physical and mental.

Cover picture : ©Cora Portais / ALIMA

¹ Source : Banque Mondiale

² Source: Humanitarian Needs Overview 2023, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, January 2023

This project received financial support from UNFPA (the United Nations Population Fund).