To start, can you explain what is dengue fever?

Dengue fever is a mosquito-borne disease transmitted by mosquitoes of the Aedes type. There are multiple symptoms such as joint pains, high fever and vomiting. Those symptoms can be relatively close to the symptoms of malaria, which partially explains the delays in terms of diagnosis. In certain cases, the fever becomes hemorrhagic and the symptoms include bleeding. The disease can be diagnosed thanks to Rapid Diagnosis Tests. Only symptoms can be treated, and the most severe cases may require blood transfusions.

The most efficient way to fight against dengue fever is to destroy mosquito breeding sites and protect the population against mosquitoes (wear long clothing, use mosquito repellent, avoid keeping stagnant water…).

Why did ALIMA and its partners decided to launch an emergency response to the outbreak?

For this epidemic, ALIMA wanted to support the Ministry of Health because really there was a gap in terms of all other support to the Ministry regarding the operations aspect, regarding the support to the hospitals, regarding the logistics aspect, in terms of RDTs [rapid diagnostic tests], in terms of drugs, in terms of laboratory analyses, exam prices and so on. For example, until we sent 2,100 RDTs, there weren’t enough tests available in the country [to correctly diagnose people]. So the authorities were happy to receive these. Also, for those patients who may not have access to health care or for patients who don’t have the means to do the exam, they now have the opportunity to do the test and have access to free care. We wanted to support the hospitals to treat the patients.

What kind of support did ALIMA and its partners provide?

In addition to sending the RDTs, we began treating patients at the end of week 45 [November 18], in Yalgado Hospital and later two district hospitals, Bogodogo and Kossodo. This included supporting the care of the most complicated dengue cases, like the hemorrhagic cases, the comatose patients, the shock cases and providing drugs. Around 70 patients were treated since we began. ALIMA and its partners also continue to support the Ministry of Health to train medical staff. We helped train nearly 300 medical staff on dengue fever prevention, how to best take care of the patients with dengue…all these things. So this training is being done and it will be important in the short- and long- terms to end this outbreak and to follow up on the disease of dengue in Burkina Faso in the future.

The second important aspect is the spraying of health centers and patients homes against mosquitoes. Thanks to financial support from ALIMA, more than 50 health structures were sprayed. This is really important if you want to end this kind of disease.

Ongoing at the same time was communication campaigns. We worked with local authorities to educate communities about dengue: what it is and how people can protect themselves, and where people can get care. This was done through animations and the diffusion of more than 7,000 posters and flyers.

What were some of the challenges?

In Burkina Faso, dengue isn’t well known. People get sick with dengue but think that the fever and headache means they have malaria and they don’t think about dengue. So they treat malaria first and think about other issues later and this delays treatment of the disease itself. Before the outbreak was declared, this created a lot of trouble for people because they waited too long to get care. This was why the sensitization messages were so important.

Also, at the beginning of the outbreak, before the response began, many people who came to the hospital couldn’t afford the treatment. So they came to this place where there they are seeing deaths but don’t have the means to buy the drugs and so they go away. We had to make sure people knew they that the treatment of simple and severe cases was free of charge in the hospitals we were supporting.

The emergency response came to an end on December 26. Was it a success?

For me, I think we had a very good impact. We helped a lot of patients, we trained a lot of medical staff. So yes, it was a success. But, but we can also say the response came a little bit late. If, for example, the intervention happened before the time it did, the impact will be even greater the next time. It’s one of the lessons learned. But this was related to the fact that it is a new disease in Burkina Faso and it’s related to the fact of what we call the “epidemic threshold” [the number of cases needed before its declared an outbreak], and for this kind of epidemic we don’t know about that. So if we don’t know that, it’s hard to come on time. But from this epidemic, we all learned from this, and next time we will know how to intervene in time and how we can come before it’s already after the peak.

ALIMA has been working in Burkina Faso since 2012. Currently, ALIMA is conducting two medical-nutritional projects in the districts of Yako and Boussé. Nearly 4,000 children with severe acute malnutrition were admitted to ALIMA’s nutritional programs between January and October 2016.

ALIMA is an independent humanitarian medical organization founded in 2009. ALIMA aims to produce quality medical care in areas of high mortality and improve the practice of humanitarian medicine by developing innovative projects. In Burkina Faso, ALIMA works with two national medical organizations, SOS Medecins and the Association Keoogo. The ALIMA projects in Burkina Faso are supported by the Office of Humanitarian Affairs of the European Commission (ECHO).

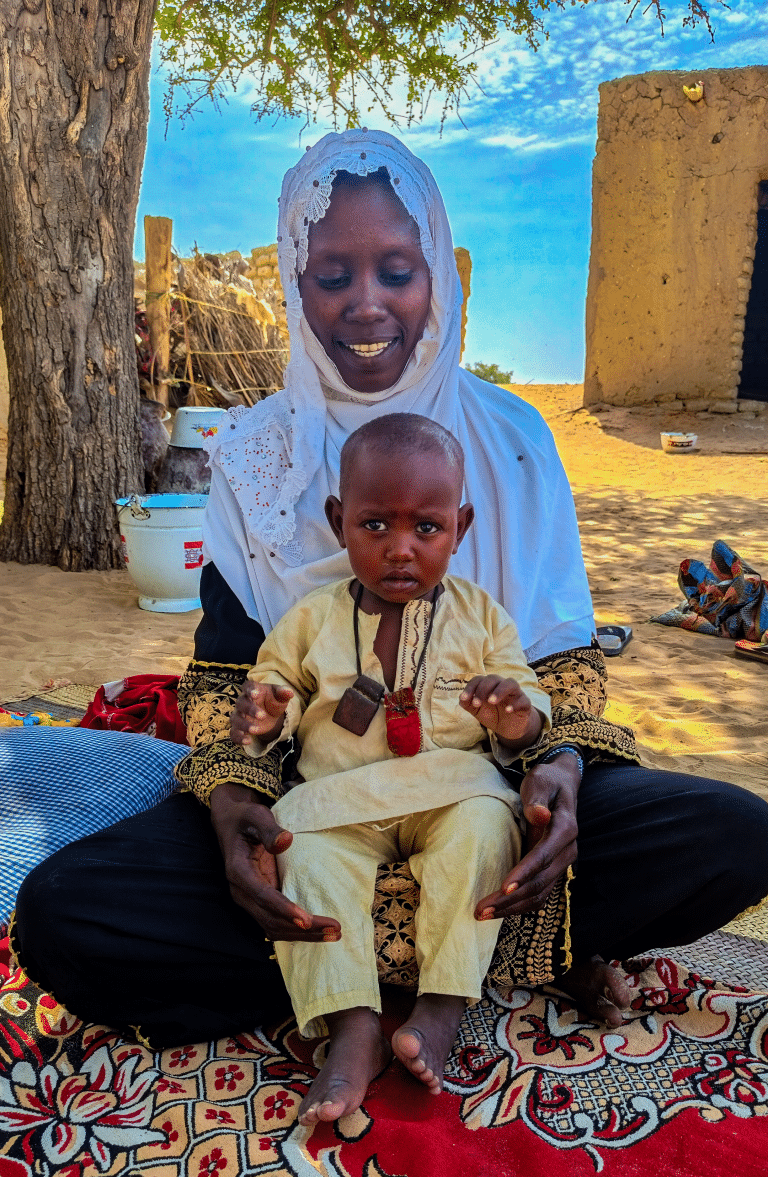

Photo: Sophie Garcia / ALIMA