“The first challenge in North Kivu was to deploy an evaluation team as quickly as possible, as time is of the essence when trying to stop the spread of an Ebola outbreak. This is no easy feat in general, and in North Kivu, given the real and complex context of insecurity, and the fact that this is was the first time Ebola was confirmed in the region, it was even more challenging. Access to certain areas was limited, and there was fear within some communities due to a lack of information. Our staff were responding not only within a context of Ebola, but also working amidst frequent attacks by armed rebel groups.

However, thanks to ALIMA’s experience responding to hemorrhagic fevers in DRC, Guinea and elsewhere, within 48 hours of the confirmation of the first case on August 1, 2018, the necessary steps were taken, alongside our partners, to launch an emergency response in the city of Beni. This included putting in place the human, logistical and pharmaceutical resources needed to open a treatment center and begin caring for patients.

The initiative to change the management and organization of the treatment protocol, particularly with the integration of ALIMA’s innovative CUBE (a Biosecure Emergency Care Unit), enabled medical teams to improve treatment management practices. Among many other advantages, the CUBE allows for more reactive patient monitoring, and interactive and comforting family visits.

This was the first time the CUBE was used to treat confirmed Ebola patients, and its integration to the response did not come without technical and logistical challenges. However, the possibility of permanently monitoring the patient in a CUBE made it possible to anticipate and manage intensive care procedures – never before envisaged at this level. Our teams continue to work to find ways to improve this innovation, which other partners are interested in replicating.

Other, new biomedical tools were also integrated during this response, such as the portable ultrasound scanner. Data management was improved via new and standardized collection methods with other partners, which provide more accurate information throughout a patient’s hospitalisation. This will allow biomedical analyses to be used to further improve clinical practices in the future.

The integration of compassionate-use therapies, and the launch of the randomized clinical trial to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of these therapies, was one of the major challenges of the intervention, due in large part to the security context and limited health resources in-country. But based on global observations, it seems to have had a positive impact on case management. At the treatment center in Beni, for example, we saw the mortality rate decrease from around 65% in August to 30% in December. The challenge now will be to meet the trail’s protocol requirements to the end.

From the point of view of the global response and the role of care, many other challenges remain, including the need to be able to deploy care more quickly than before in order to save more lives at the beginning of the outbreak. Psycho-social support, thanks in part to the proximity of the patient offered by the use of CUBE, has also progressed considerably, but still needs to be documented, as major advances have been made in this regard. We also need to document cured cases in children – who have been among the worst affected during this outbreak – particularly regarding the use of the therapies.

Finally, it is necessary to continue to build capacity and transfer skills to DRC’s local health staff, continue to ensure the safety of personnel working at the treatment center, while improving the response in general and being able to continue our work in this context of volatile security. Together, I am hopeful that we can soon bring an end to this outbreak.”

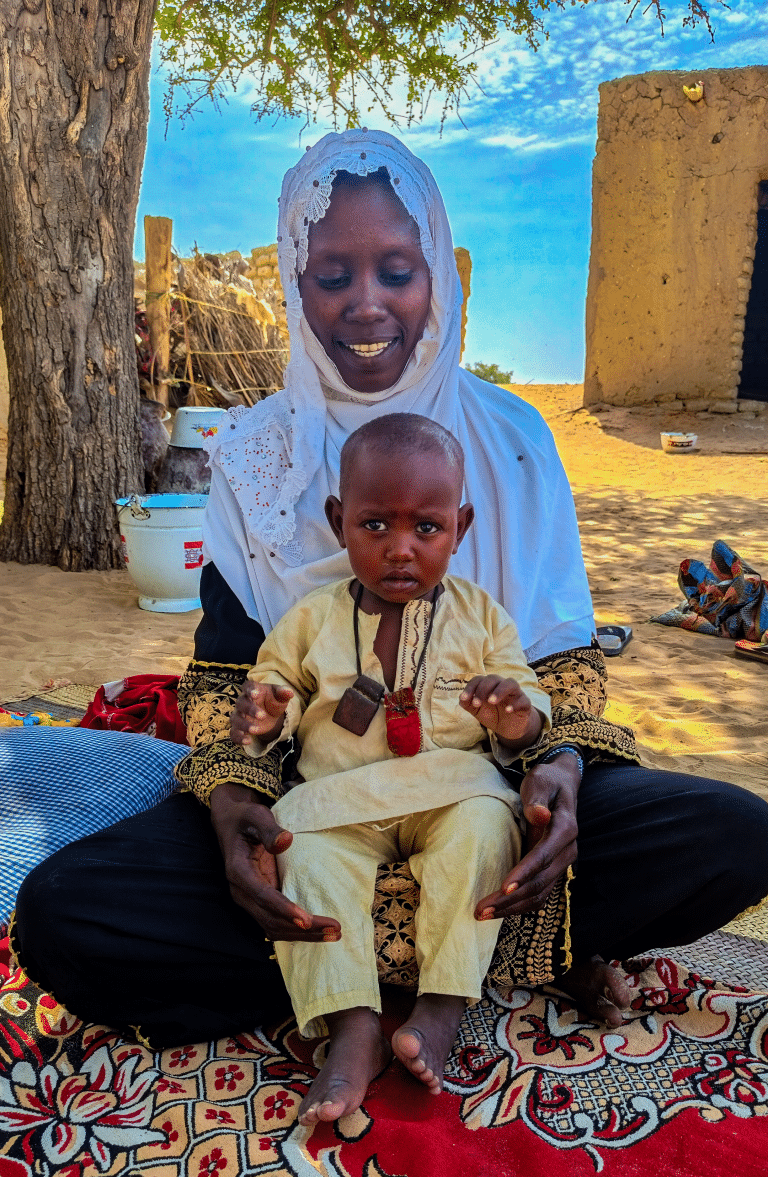

*Cover photo: Alexis Huguet / ALIMA