Dr. Karim Assani, who currently works with ALIMA as a pediatrician in Boda, in the Central African Republic, recounts this story, about a nurse intern he worked with during his time as a pediatrician in N’Zérékoré, Guinea in 2016:

“I got the call around 9pm one night. A premature baby, weighing just 1.2 kilograms, who we had admitted to the neonatal unit a few days earlier, had gone into respiratory distress. While the baby could open his eyes, move his limbs, and had a strong heartbeat, he had stopped breathing. His immature brain had forgotten that breathing is one of the tasks that it must control. In this case, we needed to find a solution to allow the baby to breathe as we waited for his brain to regain control of his lungs. The only solution was to manually ventilate the baby as long as necessary.

In the neonatal unit, the team was overwhelmed – sometimes having to care for 2 or 3 babies within the same incubator, due to a lack of bed space. So for the first hour, I helped the baby breath using a self-inflating resuscitation bag, making sure all his vital signs remained normal. But after an hour, nothing! The baby still couldn’t breathe on his own. I immediately realized that it would be necessary to keep artificially ventilating this baby. But who could ventilate this baby for a long time within the context of work overload? Perhaps a trainee, I thought.

I found a pediatrics nursing student and quickly taught her how to ventilate the baby. ‘Don’t blow too much air into the lungs, don’t ventilate too fast, or too slowly…Make sure there are no air leaks, make sure the vital signs remain in the normal zone, make sure the baby’s skin remain pink’.

After successfully learning the technique, the trainee assured me she could continue ventilating the baby until the end of the night shift. And she did! She properly ventilated the child all night. At 6 o’clock in the morning, the baby caught his first breath! It was a surprise to the whole team and the baby’s family. No one had really had hope that this child would survive.

Eventually the baby was discharged, after gaining weight and strength. He left the hospital in good health and continued to record normal health during follow-up consultations. The family was overjoyed. In the end, the nurse had played a vital role during this crucial moment of the baby’s life. His survival was thanks to her and the team.”

Caroline Kia, ALIMA nurse at the Raja State Hospital in South Sudan

“Yes, sometimes it can be very challenging to be a nurse in South Sudan, but we are used to the situation and we do our best…What I love most about being a nurse is going and being in the ward each day. Just last night, I was on night duty and we had six new patients admitted. All night, we worked tirelessly to care for them and reassure their families. By morning, I was exhausted, but I was so, so happy, because these children now have a chance at life.”

Grevisse Kahindura, an ALIMA nurse since 2011, currently managing outreach activities in Askira, Nigeria

“One of the biggest challenges of working as a nurse in a conflict zone remains the fact that the patients you are treating in these areas are traumatized. You must be able to approach them with care and compassion, and help relieve their stress, so that you can earn their trust and best treat them. The other problem is that many people in these zones are always fleeing, always on the move. Their access to medical care isn’t regular, and sometimes they are scared to come for help, and so they come too late. Or women try to give birth at home and come too late. Some health workers might blame the patient or scold them. But it is important not to judge these patients, but to still care for them, and also to receive them as a person, not as a victim of violence or as a carrier of disease. Compassion is most important, because the patient needs to be at ease. We need to put the patient first; we can’t pass judgement on their situation. Otherwise, maybe next time, they won’t return to the hospital or clinic.

Despite the challenges, I love my job. Truly. Sometimes people ask why I am still ‘just a nurse.’ ‘Why don’t I try to be a boss or run a clinic?’ But I love being a nurse. I prefer to be a nurse. I prefer to work directly with the patients, to interact with them, not just sit in an office. Because when you care for a patient and then you see them get better because of your care, it is a wonderful feeling. So I am proud to be a nurse.”

Akala, an ALIMA nurse who has been working at the Mokolo district hospital in Cameroon since 2015

“I really appreciate the technical quality of the equipment here. It allows us to resuscitate patients and provide intensive care. To revive a child, when you succeed, it makes you so happy, because one of the biggest problems here is that children often arrive too late in the hospital. Mothers keep their sick child at home, sometimes for a week, trying to treat them with traditional medicines, and then the children arrive at the hospital in serious condition.”

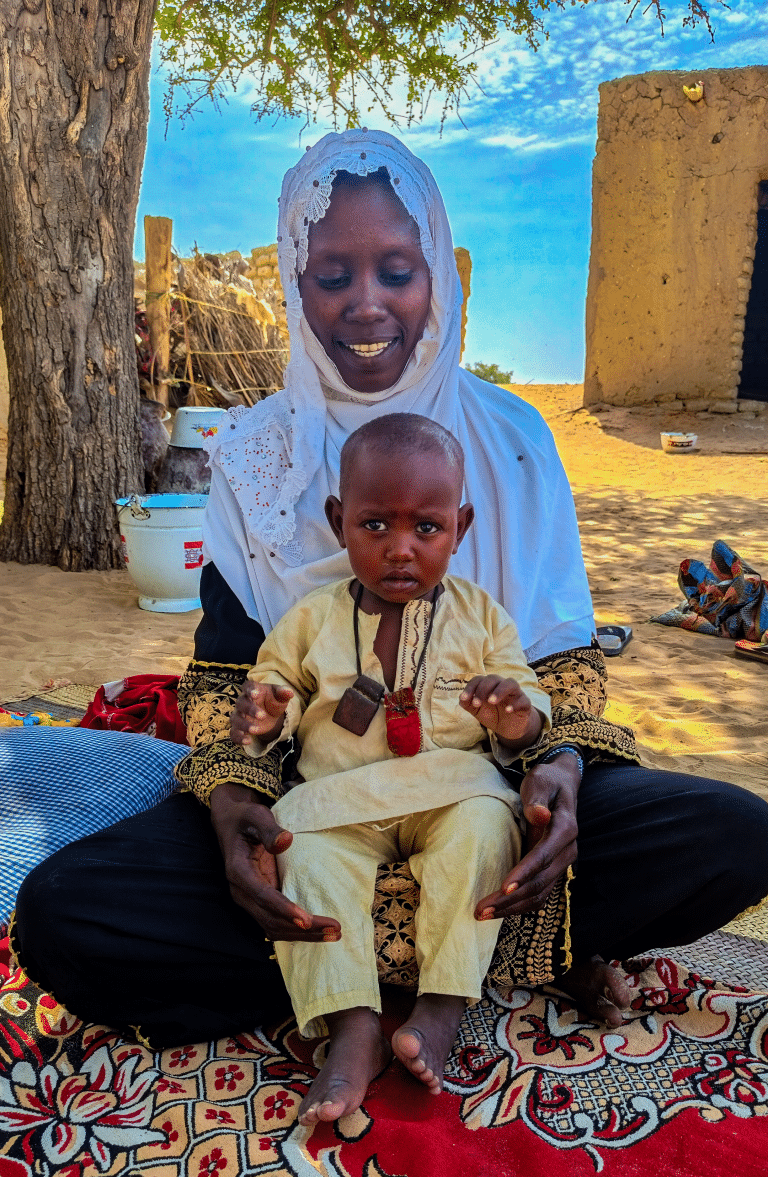

Cover photo: Nana Kofi Acquah / ALIMA,

South Sudan photo: Eymeric Laurent-Gascoin / ALIMA,

Cameroon photo: Alexis Huguet / ALIMA