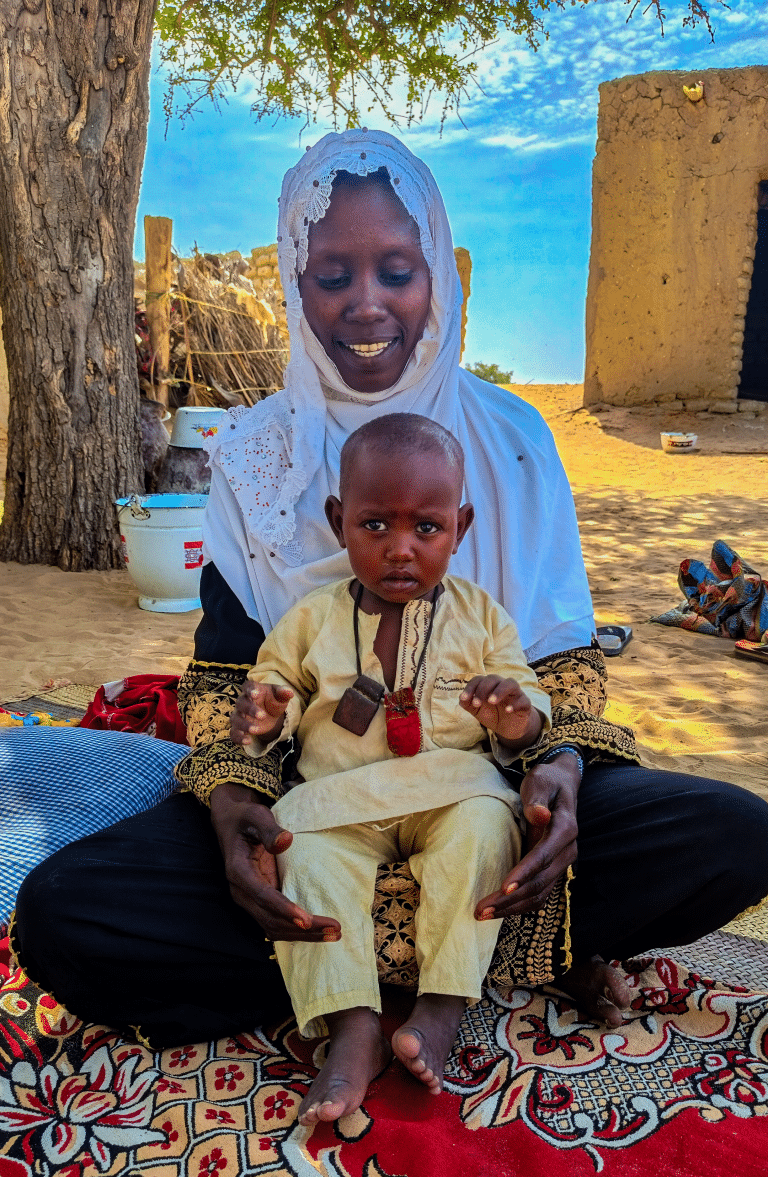

“I learned to monitor my child myself”

In N’Djamena’s Walia district, Briya holds her nine-month-old son close to her. “He got sick a week ago. The doctor said it was malaria and acute malnutrition,” she explains. Acute malnutrition cases are all too common here. In 2024, 11.4% of children in N’Djamena province suffered from acute malnutrition, with 2.7% affected by the most severe form (SMART survey).

What prompted Briya to quickly take her son to the health center was her vigilance, a skill she developed in recent months through the weekly visits to the neighborhood of community health workers from ALIMA and Alerte Santé, a Chadian NGO partner.

“Thanks to the community workers, I learned how to use the MUAC [mid-upper arm circumference] bracelet. I often measure his arm and know when to act fast.”

This colored bracelet – green, yellow, or red depending on a child’s upper arm circumference – has become a common tool in many homes in N’Djamena’s 9th district. Its use at the household level is crucial to prevent severe and even fatal forms of acute malnutrition.

An important community network supporting families

“Consolé has rather weak health,” says 29-year-old Miliwam. “The women in the neighbourhood told me about ALIMA, Alerte Santé, and the community health workers they work with. I met them during one of their visits here. Their advice was really useful to me: on hygiene, nutrition, and more.”

“Tomorrow, I’ll do my best to go to the health center. My little one has been unwell for weeks. Maybe it’s malnutrition, maybe something else, I don’t know, I’ll find out tomorrow.”

Like Milliwam, Bella also decided to take her 10-month-old daughter to the health center, after observing her for a few days:

“My husband and I noticed she was losing weight because of diarrhea. We had been made aware of the signs of malnutrition. So we brought her here, to the Toukra health center.”

The health center, a place of treatment…

At the health center, ALIMA / Alerte Santé’s medical staff took care of her daughter, examined her, and diagnosed her with acute malnutrition. Bella and her baby will be able to go home with the treatment, ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF). They will have to come back every week, to monitor the child’s health, and receive the RUTF ration for the following week until full recovery.

“After three weeks of treatment, I’ve seen real progress. Currently, her weight is stable and I hope she’ll continue to gain fast.”

… and awareness

Prevention is everyone’s business, everywhere. At the health center, women who have not yet been trained to use the MUAC bracelet are introduced to it and receive one to take home.

At the Ngueli health center, Amina, a mother of two, has just returned from a cooking demonstration organized by community health workers. “I often make porridge, but I’d never seen it prepared this way. It is good for children. If I can get all the ingredients, I’ll make it again at home.“

“Watching over our children’s health”

For Maïmouna Hassan, a farmer, the visits and awareness raising of community health workers have been life-changing for her and life-saving for her child. “My son has been unwell since birth. I received the MUAC bracelet here and now regularly check him at home. My son joined the nutrition program a month ago, and since then, he’s regained some strength. I also prepare the porridge I learned to make here.”

This connection between the population, community health workers, and health centers is at the heart of the community-based approach. The stakes are crucial as the peak period of malnutrition approaches, when food supplies are low before the next harvest.

To tackle the growing malnutrition crisis and support vulnerable populations, vigilance and action must be a shared responsibility.

The fight against acute malnutrition also takes place there: at the threshold of every home in the neighborhood.

Photo credits for this article: Daniel Beloumou / ALIMA