How important are vaccinations in the countries where ALIMA works?

Nafissa Dan-Bouzoua: ALIMA works primarily in areas in West and Central Africa where infectious diseases, such as measles, meningitis, and others, are endemic or epidemic. What’s more, we primarily work with the most at-risk groups, like children and pregnant women. Vaccination remains one of the most effective means to protect against infectious disease, but for the most part, people still remain very poorly covered by vaccination.

And why is that?

NDB: People in West and Central Africa have a real problem accessing health centers. Even though vaccinations are free in most countries, and there is a lot of effort to vaccinate people, there are still remote areas that are difficult to access, due to their location or due to security risks.

Furthermore, sometimes vaccines are just not available or there is no way to store them. Health systems are weakened by a lack of staff, who are overloaded with multiple responsibilities.

How can we improve vaccination coverage through research?

Susan Shepherd: Given all of the difficulties that we have in providing proper care in the contexts in which we work, in West and Central Africa, prevention is even more important than in areas with good health services. And yet we are faced with a major dilemma. Research teams who, understandably, want as much control over a study’s circumstances as possible, tend to conduct much of their research in countries like Ghana, which has a relatively strong healthcare system and few security problems.

And of course, that’s great for Ghana. But we shouldn’t exclude from the outset the countries with weaker healthcare systems from participating in operationalizational studies, because that’s exactly where we make the greatest difference. I would cite the Democratic Republic of Congo and Guinea as two countries that are prime examples of where I believe that it is possible.

NDB: Not only do we need to make vaccines available but we need to improve storage methods. One effective strategy is to combine activities, meaning take advantage of any opportunity to vaccinate the population. For example, ALIMA will take advantage of food distributions or malnutrition screenings to conduct vaccination campaigns.

What impact do vaccinations have in the areas where ALIMA works?

NDB: Vaccines protect against diseases that can have serious, sometime fatal consequences.

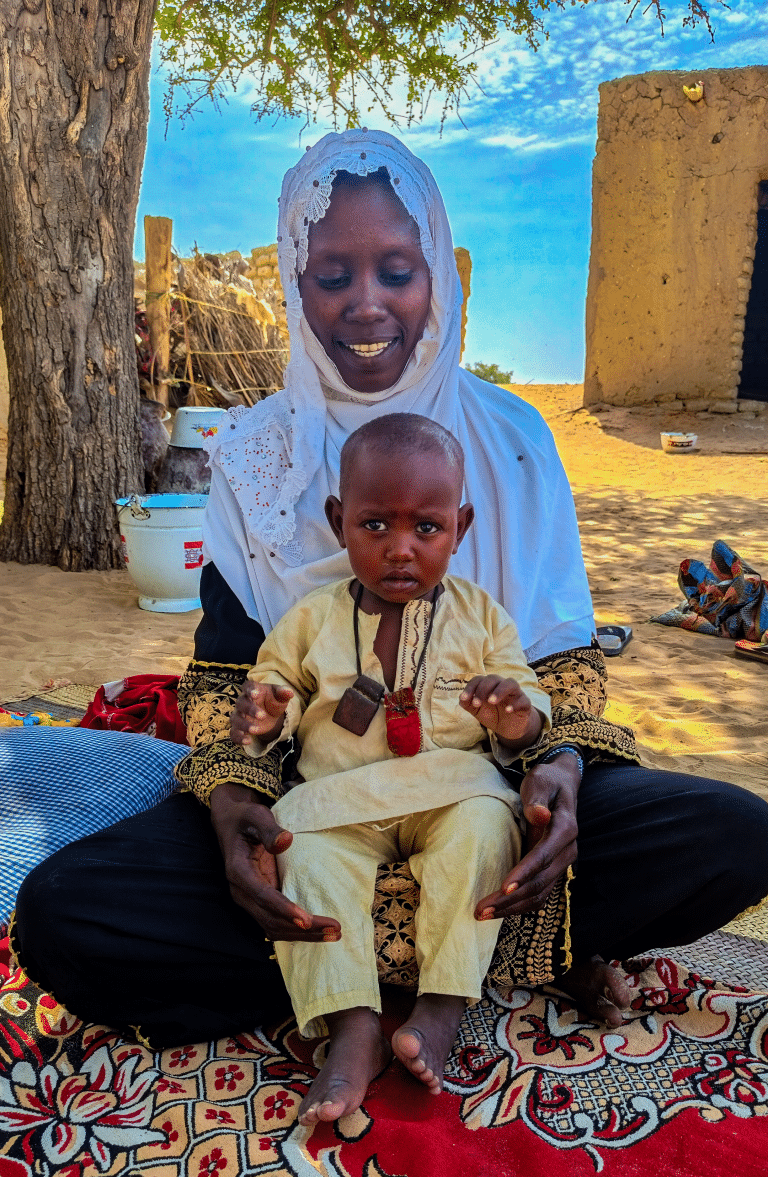

SS: I would mention the 1,000 Days program, a comprehensive pre- and post-natal care package for pregnant women and their children that introduces free, routine vaccines into our programs. In the places where this program is implemented, the percentage of children who receive all their vaccines surpasses 80%, which is among the highest vaccination rates in Africa.

It’s a virtuous circle where children are protected and therefore less often sick, and less often affected by infectious disease. With fewer episodes of illness plus an enriched diet, they are far less likely to suffer from acute malnutrition.

To conclude, is there anything else about vaccinations that needs more attention?

SS: The last thing I would mention, is that while we are constantly addressing vaccination, routine vaccinations, the expanded program on immunization, there is relatively few research initiatives that try to be more creative in trying to access children.

The 1,000 Days program is just one way of increasing the number of chances to vaccinate. But there is really very little in the way of operational research that tries to find other ways to increase the number of vaccination opportunities, either by finding new opportunities or by making vaccines more useful.

Another issue is vaccine wastage. Usually a vaccinator will not open a vial unless they are assured of using more than half of the doses. For example, the vaccine against measles comes in a vial with 10 doses. This means that the person vaccinating will not open the vial unless there are five children to vaccinate present. It could be something as simple as making smaller vials.

It’s this kind of practical research, with simple ideas, that can increase the number of children who are fully immunized at the correct age.

ALIMA (The Alliance for International Medical Action) is a medical humanitarian organization that aims to provide assistance to populations in emergency situations, such as epidemics, conflicts or natural disasters. Based in Dakar, Senegal, ALIMA has treated nearly 3 million patients in 12 countries since its creation in 2009, and launched 10 research projects focused on malnutrition, malaria and Ebola.

In 2017, ALIMA provided routine vaccinations for more than 100,000 children in 6 countries in West and Central Africa (Mali, Niger, Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Central African Republic, and Chad), against diseases such as measles, meningitis, polio and tetanus. In 2017, ALIMA responded to an outbreak of measles in Guinea, working with the Ministry of Health to launch an emergency vaccination campaign in the southeast region of N’Zérékoré, which reached more than 148,000 children. In Nigeria, in partnership with the Ministry of Health, ALIMA conducted a campaign to vaccinate for meningitis and measles, where more than 96,000 children were vaccinated against meningitis and more than 35,000 against measles.

Photo: Nick Loomis / ALIMA